After the Alter Rebbe left this world, Rabbi Dov Ber (1773-1827), known as the Mitteler Rebbe (Yiddish for "the Middle Rebbe"), became the leader of the Chabad movement. Since he was the son of Rabbi Shneur Zalman, he was occasionally called Rabbi Dov Ber Shneuri, however the family name of the Chabad dynasty only became Schneerson in the time of his son-in-law, the Tzemach Tzedek.

Like his father, the Mitteler Rebbe not only developed and disseminated Chassidic philosophy; he also made extensive efforts to provide material and spiritual help to needy Jews.

In 1814, he founded a Chabad center in Lubavitch (now in the Smolensk district). This town provided the Chabad movement with its second name, serving as its headquarters for close to 102 years, until 1915.

The life of the Mitteler Rebbe was similar to his father's. He too was arrested on false charges, in 1826. As in the case of the Alter Rebbe, he was accused of channeling funds to the Turkish sultan, the czar's enemy. Eventually, like his father before him, he was completely exonerated and released. The Mitteler Rebbe left this world soon after his release, in 1827.

The third Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel (1789-1866), was the son-in-law of the Mitteler Rebbe and the grandson of the Alter Rebbe. His erudition was extraordinary even for a Rebbe, and he introduced a number of new and particularly sublime ideas into Chabad philosophy. He is known as the "Tzemach Tzedek" after the opening words of his magnum opus. Significantly, Tzemach is one of the traditional Jewish names for Mashiach.

The Tzemach Tzedek was incredibly knowledgeable in Chassidism, Talmud, Kabbalah, and halachah. His book Derech Mitzvotecha is an analysis, from the Chassidic viewpoint, of all the various approaches to and interpretations of the fundamental ideas of the Torah. However his fame, like that of his predecessors, was based not only on his erudition, but also on his practical efforts on the behalf of the Jewish people. Inaddition to numerous educational institutions, he established agricultural settlements where impoverished and starving families could find a steady and honorable livelihood.

During the time of the Tzemach Tzedek, the so-called maskilim, the adherents of the Haskalah (Enlightenment movement), whose goal was to introduce the Jews to "world culture," attempted to reform the traditional system of Jewish education. They sought to introduce secular subjects, taught from an atheistic viewpoint, to the curricula of Jewish schools. The Tzemach Tzedek spearheaded the struggle against these endeavors, with their inherent danger of mass assimilation. He succeeded in rallying the support of all the opponents to the reform, including some prominent rabbis from among the mitnagdim. The efforts of the Tzemach Tzedek won him enormous popularity in every sector of Torah-observant Jewry. As a result, even the czarist authorities were forced to recognize his special status, awarding him the title of "honorary citizen of the Russian Empire." All the subsequent Lubavitcher Rebbes inherited this title.

Another heroic act of the Tzemach Tzedek was the rescue of thousands of Jewish children from the perils of forced conversion and even death. In 1827, Czar Nicholas I issued the infamous conscription decree, under which all Jewish boys twelve years of age and older could be drafted into the army. Responsibility for enforcing this decree was placed on Jewish communities, which were required to fill a conscription quota of ten boys for every thousand Jewish residents. Even though a similar law was issued for gentiles, the quotas were lower, and it provided for various privileges and exemptions.

When it was discovered that most of the Jewish communities were trying to evade this brutal decree, the government dispatched secret agents to towns and villages to hunt down the draft dodgers. Thousands of small boys some of them barely seven years old - were seized and forcibly sent to orphanages or peasant families, where they would be kept until the age of twelve. At that point, they were sent off to military barracks. At the age of eighteen, they would embark on twenty-five years of regular military duty. The majority of these boys never made it back to their families. As a rule, children's freedom could be bought by bribing the czarist "snatchers," but the families were so desperately poor that this avenue of escape was out of the question. The conscription decree caused deep dismay among Russian Jewry; people vainly looked for ways to save their children. The Tzemach Tzedek founded a clandestine society known as "those who raise the dead" for the rescue of kidnapped children. They monitored all that was happening to the conscripted children, raised money, bribed czarist officials to issue falsified death certificates, and when the time was right, ransomed the boys. In this way, thousands of stolen children were saved.

The Tzemach Tzedek had seven sons. The youngest, Rabbi Shmuel (1834-1882), was designated by the Tzemach Tzedek to become the fourth Lubavitcher Rebbe. Rabbi Shmuel assumed the leadership of the Chabad movement in 1866. During that time, anti-Semitism had reached unprecedented proportions in Russia. Pogroms, looting, and abuse of the Jews became commonplace phenomena. In most instances, the ruling elite instigated the persecutions. Thanks to the prestige he had won in the highest circles of Russian nobility, the Rebbe managed on more than one occasion to protect Jews in many towns and villages. Moreover, he often did so at risk to his own life.

The concept of le'chatchilah ariber, a Yiddish expression meaning "to leap over obstacles from the start," was introduced into Chassidic practice by Rabbi Shmuel. According to this approach, if a Jew comes upon an obstacle, he should overcome it in the most direct manner, leap over it, as it were, rather than go around or under it. The Rebbe would often demonstrate to his Chassidim the practical application of this principle.

The fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe was Rabbi Shmuel's son, Rabbi Shalom Dov Ber, known by the acronym Rashab (1860-1920). One of his major accomplishments was the establishment of the famous Lubavitch yeshiva, Tomchei Temimim ("bulwark of the open-hearted," or "the pure"), as well as a series of other yeshivot throughout Russia. These institutions raised the level of Torah learning to new heights, particularly in areas far removed from Jewish centers, such as the Caucasus.

During World War I, when the German army was approaching Lubavitch, Rabbi Shalom Dov Ber moved the Chabad headquarters to Rostov-on-Don in southern Russia. Soon afterwards came one of the most tragic events in the history of mankind in general, and the Jews in particular the communist revolution in Russia. The following amazing story happened at that time.

During World War I, a religious Jew who resided in one of the Russian cities disappeared without a trace, leaving behind a wife and small children. His wife looked for him everywhere to no avail. She had almost lost all hope when a friend from Chabad advised her to go to Rostov-on-Don to see the Rebbe Rashab. "He is the only one in the world who can help you," the friend told her.

The woman went to Rostov, where she tried to make an appointment to see the Rebbe, however, she was bitterly disappointed. "The Rebbe does not receive women," she was told by the Rebbe's secretary. "You can write a letter to the Rebbe. I will take it to him and give you his reply."

The woman tried to explain that she had to talk to the Rebbe in person, but the secretary was adamant. She had no choice but to relate her sad story on paper, asking the Rebbe to help her find her husband.

Some time later, the secretary brought her the Rebbe's reply: she was to go to Warsaw, where she would find her husband.

The woman was astonished and dejected; how would she ever get from Rostov to Warsaw, when the country was ravaged by war and dangers lurked at every step? Besides, she had no money for such a lengthy trip. However, the Chassidim at the Rebbe's house assured her that if she really wished to find her husband, she had to act on the Rebbe's advice. Without further ado, they pooled their money to provide for the trip.

Without having seen the Rebbe, the woman set out on her journey. When she finally arrived in Warsaw, she stood at the train station at a loss as to where to go and what to do. She did not know a soul in Warsaw, and the Rebbe had not mentioned any contacts in his letter.

Suddenly a tall, dignified looking Jew with a light beard approached her and said, "I see that you are in need of help. Can 1 be of service?"

The woman related her story. The man asked for her husband's name, and then suggested that she should go to a mill nearby, and inquire there about her husband. After giving her directions to the mill, the man wished her luck and went away.

When she found the mill, the woman asked the owner whether he had any knowledge of her husband. "Of course!" exclaimed the miller. "He is one of my workers!" He left, and returned a few minutes later accompanied by the woman's husband.

Their conversation was brief. The husband explained that he had no choice but to flee Russia. The woman, on her part, urged her husband to come back, but he insisted that he was afraid to go back to Russia. Finally, he asked his wife how she had managed to find him, and she told him about her visit to the Lubavitcher Rebbe, and his advice to go to Warsaw. Upon hearing this, the husband said, "If there is a tzaddik capable of finding me from a thousand miles away with his holy sight, I am ready to go back!" They returned to Russia, where they lived in peace for many years.

However, the story does not end there. Upon her return, the woman went back to Rostov to thank the Rebbe. As before, she was told that the Rebbe did not receive women, but she insisted on telling the Rebbe her good news in person. The Chassidim suggested that she wait by his office door at the time when he usually came out. The woman did just that.

When the door opened and the Rebbe stepped outside, the woman cried out, burst into tears and, collapsed in a faint. When she regained consciousness, the Chassidim questioned her what had caused her such a great shock. "Don't you see!" exclaimed the woman. "This is the very same man who came up to me at the station in Warsaw and helped me find my husband!"

"You must be mistaken," the Chassidim objected. "The Rebbe has not been to Warsaw for quite a while."

Still the woman insisted, "This is the same man! I am not mistaken!"

The Chassidim inquired about the exact time she had met this man in Warsaw. The woman told them the day and the hour she was approached by that "tall, dignified looking Jew with a light beard" at the Warsaw railway station.

An amazing discovery came to light. The Rebbe followed a very strict schedule. Although he devoted very little time and attention to eating, he took his meals punctually at one in the afternoon every day. The secretary would bring his meals to the office, the Rebbe would let him in, the secretary would place the food on the table and leave.

On the day the woman encountered the tall Jew in Warsaw, a strange occurrence took place in Rostov. When the secretary brought the meal at the usual time, the Rebbe did not open the door and did not respond to the secretary's knocking. The door was locked from the inside. A few minutes later, the secretary knocked again; there was no response.

The Chassidim were seriously concerned that something might have happened to the Rebbe. After all, he had never failed to open his office door before. One Chassid went to the office window, which faced the street. The curtain was drawn. He climbed the wall and peered into the Rebbe's office over the curtain. He beheld a strange sight: the Rebbe was leaning on the windowsill, standing and gazing into the distance. His face was pensive and absorbed; it was obvious that his thoughts were somewhere far away. After a long time the Rebbe opened his office door and asked for his meal to be brought in.

By comparing the dates, the Chassidim ascertained beyond any doubt that it was precisely when the Rebbe had stood lost in thought by the window of his office in Rostov that the "tall, dignified looking man with a light beard" had come up to the woman at the Warsaw railway station.

The son of Rabbi Shalom Dov Ber, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak (1880-1950), became the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe after the passing of his father in 1920. This was a turbulent time; the violence of the Bolshevik revolution and the brutality of the infamous Yevsektzia (the Jewish Section of the Communist Party) were at their height. Joseph Stalin and his Jewish right-hand man, Shmuel Agursky, established the Yevsektzia in 1918 with the goal of killing the soul of Russian Jewry. Even prior to assuming the Chabad leadership, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak, in his capacity as his father's assistant and envoy, had weathered many storms to emerge as a capable leader. One of the main areas of his activity was strengthening the Chabad yeshivot, which provided Jewish education to numerous students who went on to serve as teachers and mentors for the entire European Jewry. He did a great deal to improve the social and economic condition of the Jews. One of the ways he did so was by resettling the Jews in areas where they could engage in agriculture. Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak spent a great deal of time traveling to the most remote and neglected areas, wherever there was a need to take immediate action to improve Jewish life.

There are numerous Chassidic stories about the amazing courage and inventiveness displayed by Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak even before the revolution, when he was acting on the behalf of his father, the Rebbe Rashab. On a number of occasions, when Jewish lives were at stake, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak managed to secretly penetrate the offices of czarist ministers (specifically, the office of Stolypin, the brutal anti-Semitic minister of internal affairs), find confidential papers containing anti-Jewish regulations, and delay their progress through the bureaucratic channels.

Like his predecessors, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak also acquired first-hand knowledge of czarist prisons. Even before he became the Lubavitcher Rebbe, he was arrested five times for "illegal" involvement in the affairs of his fellow Jews throughout Russia. Before the revolution, the main threats facing Russian Jewry were poverty and pogroms. With the revolution came the added reprisals carried out by the Yevsektzia. It is no surprise that the agents of the Yevsektzia viewed the Lubavitcher Rebbe and his followers as their worst enemy, bent on fostering and supporting a Jewish way of life based on Torah commandments.

In 1921, the Rebbe established a yeshiva in Rostov. This was used as a pretext for yet another arrest on charges of treason against the Soviet government. The Rebbe was subjected to lengthy interrogations; brandishing guns, the interrogators tried to intimidate him into signing a confession. Naturally, the Rebbe flatly refused.

Before long the Rebbe was released, to plunge once again into feverish activity. At a time when the majority of Jewish leaders either left the country or were immobilized by fear, the Rebbe sent envoys to every comer of the Soviet Union with instructions to do the seemingly impossible: to establish new underground yeshivot and Torah schools, to build mikvaot, to utilize every opportunity to foster Jewish education and Torah observance.

One night early in the summer of 1927, agents of Tcheka (the Soviet secret police) and the Yevsektzia broke into the Rebbe's home in Leningrad. They searched for several hours, The secret police tried everything to humiliate the Rebbe, including rude and abusive behavior. In the predawn hours, he was taken away to one of the most gruesome detention centers - the infamous Shpalernaya prison.

The interrogations were once again full of the usual threats and intimidation techniques. "This little toy," said the investigator as he pressed the barrel of a gun against the Rebbe's chest, "has made many a man change his mind."

"This little toy," replied the Rebbe, "can intimidate only the kind of man who has many gods and but one world. Since I have only one G*d and two worlds, I am not impressed by your little toy."

The "trial" was held several days later, and the Rebbe was sentenced to death. He was placed in solitary confinement. Would the Bolsheviks have the audacity to carry out the sentence? The mere thought that the Rebbe could be executed horrified both his thousands of Chassidim and countless other Jews. Leading politicians, heads of government, and presidents of various countries tried to intercede with the Soviet authorities on the Rebbe's behalf. Millions of Jews were praying for the Rebbe, and their prayers were answered. For the first time in history, the Bolsheviks had to concede defeat. The death sentence was replaced, first by imprisonment on the Solovetzky islands, and then by exile to Kostroma. Ten days later, on the 12th of Tammuz, The Rebbe’s birthday, he was completely acquitted and released.

The joy and gratitude following the Rebbe's miraculous deliverance knew no bounds. The Bolsheviks were not all-powerful after all. The iron will and un shakable faith of one truly spiritual man had overcome them! Clearly, despite the horrors of the Soviet regime, the future and destiny of Soviet Jewry were not as hopeless as they had seemed.

The Rebbe left Kostroma and settled in the village of Malachovka, in the vicinity of Moscow. Giving way to the relentless pressure of the international community, the authorities gave the Rebbe permission to leave the Soviet Union for Riga, the capital of still independent Latvia. He demanded that the authorities provide him with several freight cars for his enormous library, which contained invaluable books and numerous unique manuscripts.

The Rebbe Yosef Yitzchak may have left Russia, but this was not the end of the Russian chapter of Chabad history; everything the Rebbe achieved, as well as the miracle of his freedom, was to have a lasting effect on the future of Russian Jewry.

In 1929, one year after arriving in Riga, the Rebbe Yosef Yitzchak took a trip to the United States, where he stayed for ten months. One of the main goals of his visit was to rally public support in defense of Soviet Jewry. While in the United States, the Rebbe was received by President Hoover. However, he attached primary importance to his meetings with Jewish public figures and countless ordinary Jews, aimed at clarifying the situation concerning Jewish education, religious and social life.

Following his return from the United States, the Rebbe remained in Riga for several years, until 1933, when he moved to Warsaw. Two years later, the Chabad headquarters were relocated to Otvock, a small town in the vicinity of Warsaw, where a Chabad yeshiva had been established twelve years earlier.

At the outbreak of Word War II, the Rebbe was in Warsaw. Together with his Chassidim, he witnessed the terrible siege of the city and its eventual capitulation to the Nazi invaders. From his shelter, he supervised the evacuation of hundreds of Jews, especially young men, to safer areas, including helping a large group of American yeshiva students leave the country. Eventually, at the start of 1940, the Rebbe left Poland for Riga, where he spent the next two and a half months. Several months before the Soviet Union annexed Latvia, the American government helped the Rebbe move to the United States. The Rebbe foresaw that the United States would become the stronghold of world Jewry in general, and of the Chabad movement in particular.

The Rebbe arrived in New York on March 19, 1940. At the port, he was enthusiastically welcomed by thousands of Chassidim and other Jews. Many of them had recently escaped the Nazis with the Rebbe's help. Immediately upon arriving at the hotel, the Rebbe announced that he would not rest or sleep until the first Chabad yeshiva was created in America. The next morning the first ten students of the new Tomchei Temimim yeshiva began their studies.

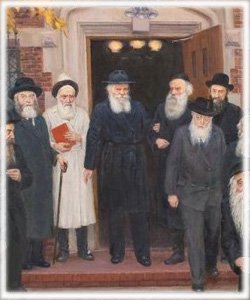

Six months after his arrival, the Rebbe moved into a building at 770 Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights, which serves as Chabad world headquarters to this day. From here, the Rebbe continued to spearhead the enormous task of saving thousands of European Jews and aiding countless refugees. He supervised the process of reconstructing the ruined Jewish communities of Europe, as well as reviving and expanding the Chabad movement, which had survived the ravages of Stalinist terror and the Nazi extermination campaign.

It is difficult to list all the educational institutions, publications, organizations, and special projects created and supervised by the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe. We will mention only some of them: the Hakriah Vehakdushah monthly official organ of Chabad, published during World War II; the Machaneh Israel organization founded to assist Jews in reclaiming their Jewish identity, learning Torah, and performing good deeds; a network of Lubavitcher yeshivot in Brooklyn, Pittsburgh, Wooster, New Haven, Montreal, and other cities; the Merkos L'Inyonei Chinuch center for Jewish education; schools for Jewish girls, the largest among them Beth Rivka in Crown Heights; the Kehot Publication Society, the world's largest publisher of Chassidic books, including discourses, articles and books written by the Rebbes; a special project for hosting children from non-religious homes by Chassidic families for Shabbat; and a project for saving North African Jewry (mainly the Jews of Morocco). These and more formed the foundation, the infrastructure of a worldwide organization, which is still in the process of constant consolidation and expansion. This was the answer given by the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe to the calamities unleashed by Stalin and Hitler.

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak left this world on the 10th of Shvat, 5710 (1950).

|